Urban Design and 'Utopia'

Modernist Pioneers like Le Corbusier and Mondrian believed in cities that consisted of straight lines and buildings arranged in geometric shapes. They also believed in the removal of decoration and embellishment from buildings. This is understandable in the context of the age they were in because elaborate and embellished buildings were a symbol of old aristocratic and imperial social structures and beliefs. Clean lines and simplicity were, to them, a sign of the democratic and proletariat values of equality.

However, decades on from their visions we can see that their plans for their ideal cities have been a failure where they have been realised, and can be envisaged as being a failure where they haven't but very nearly were. They thought they were being scientific and that the human mind would draw some refreshed sense of purpose from living in a symmetrical city but they failed to realise that the human mind actually likes embellishment and decoration. A Treaty on the Ideal City, were one to be written today, would probably conclude that beauty and interest does not involve straight lines and symmetry. In fact, visual beauty was identified by the ancient Greeks in the Golden Ratio which is 1 to 1.62, which does not represent a regular geometric ratio. Images that conform to this number are seen by people as more visually pleasing. Any building that conforms to this ratio would definitely not be clean and without embellishment.

The human mind does not like perfect symmetry or simplistic geometrical shapes. The same can be seen in music where phrases that have a bar missing or an extra one added are more interesting and appealing that something totally rigid in structure. I also believe it applies to the layout of cities as well.

I remember thinking how well laid-out the city centre of Liverpool is, apart from one area between the business district and the main shopping area. There seemed to be a permanent lack of people walking through and it felt like a dead area. This area is where the new Liverpool One shopping centre is now located. This has brought a dead area back into use and the whole city centre now feels like it has a lively footfall and an interest. The recent decline in High Street shopping generally has meant some areas, such as Bold Street on the other side of the centre, have declined in vibrancy, but this is a problem that every city centre is having to deal with. It got me thinking that you could plan a city centre based on ensuring that all areas are laid out to encourage maximum footfall to avoid leaving some areas feeling dead. Sheffield has one of the most disjointed and unappealing city centres in the country and could do with some analysis of this kind to create a long-term plan for urban regeneration.

I thought I was on to something new with this idea until I saw a programme about the plans for the redevelopment of London after the Great Fire in 1666. It seems Cristopher Wren had the same idea with his plans. The programme featured a business that had a formula for working out footfall based on the principle that people will always seek what is perceived to be the quickest route from A to B. They compared Wren's plan with that of Robert Hooke and John Evelyn.

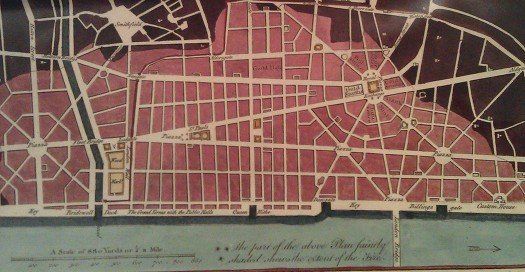

Wren's plan would have resulted in maximum footfall around St Paul's Cathedral and the Royal Exchange, which is no doubt exactly what he intended, and would have had very few dead areas resulting in an exciting, lively city:

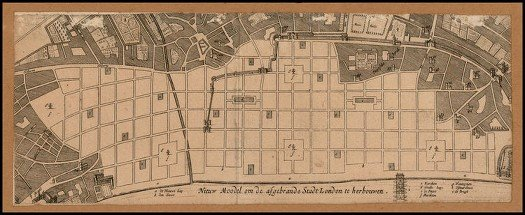

Robert Hooke's grid system, in contrast, would have lacked a focal point and resulted in many dead areas within the city:

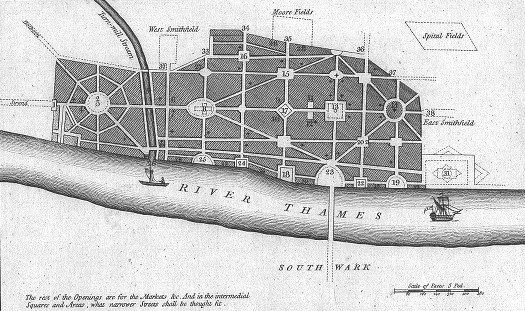

And John Evelyn's plan would, according to the analysis, have produced a lot of activity around the edges and only a couple of busy areas within it:

It is a testament to Wren's genius that he understood how to create a busy city and produced a design that would have been a great success, had the city been graced with the time and money to put it into practice.

Achieving a busy city is not a problem for somewhere high-rise and densely populated like New York because the sheer numbers of people will eliminate any dead areas before they are formed, but elsewhere urban planners should think hard about how to ensure that every square inch of a town has life in it, even if that means the deliberate creation of some quieter areas where people who have to make a conscious effort to frequent.

Planning a city can now been seen as a science with footfall carefully predicted, in ways far better than the supposed scientific cities envisaged by the Modernists. Erratic street plans will often make for a more interesting city than a simple grid system by creating cosy and interesting parts of a town to contrast with grander boulevards. The human mind prefers some variety but within a overall recognisable structure and framework, and this applies to the arts and the built environment alike.

In recent years there has been an effort to eradicate much of the failed post-war urban planning failures in the UK, and following the rise in internet shopping and the consequent decline in city centre shopping cities are having to reinvent themselves. By applying a scientific approach to predicting the movement of people, and in achieving the right balance between ordered streets and variety, it should be possible to create city centres that feel busy and are places that people will naturally gravitate towards. The aims of the utopian planners of the past can be realised, but with outcomes very different from their grandiose plans.